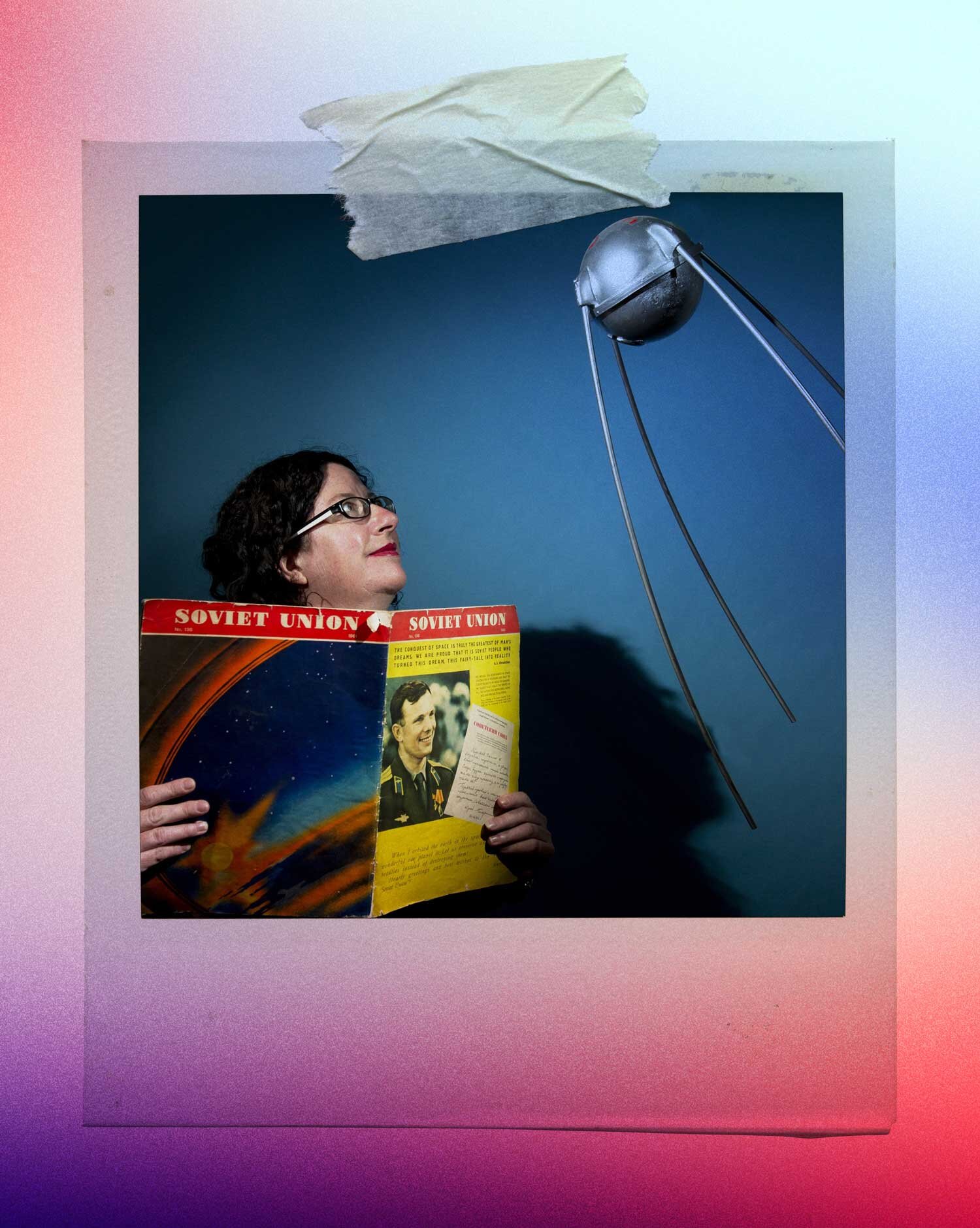

Agent Of Change: Alice Gorman

From moon bases to missions to Mars, everybody’s talking about space. For Flinders University associate professor Alice Gorman, however, it’s not only the future that excites. Her work delves into the hidden history of space exploration and what it tells us about human society and culture.

You started in archaeology, researching Indigenous sites. Switching to space was an unusual move.

I’ve always been interested in what’s above us. When I started reading about Australia’s space history, I thought about the fact that we built this massive rocket launch site, Woomera, in the middle of Australia and I wondered – where are the owners? When you go to Woomera, you meet traditional owners still living in the area and you look at the ground and see stone tools everywhere, deep evidence of deep Aboriginal occupation of country.

So Indigenous history and the history of the space age co-exist?

Absolutely. When governments were seeking empty land for rocket launches, they often used land from which people had been deliberately removed. Russia’s first rocket launch site in Kazakhstan involved a similar process: the nomadic people who occupied the steppe regions – moving seasonally with their herds – were displaced. When we talk about the effects of colonialism on indigenous people, it doesn’t stop at the edge of the atmosphere. No-one is compensating indigenous people for the use of their lands for the development of rockets.

Most of us don’t think of Australia as having much to do with space exploration – apart from what we saw in The Dish, that is.

Australia has an incredible space history. The Apollo moon landings are seen as a US achievement but there were all kinds of contributions made by various countries including Australia. We have traditionally had a very close relationship with the US and have worked closely with them from the beginning of the space era. We have tracking stations in most states as well as research and development sites. The testing we did for them at Woomera was just the start.

How do you study space technology – spacecrafts, satellites, space stations and other infrastructure – when most of it floats above our heads?

As an archaeologist, you usually engage with things on a human scale: ceramics or stone tools made to fit in a human hand, houses or landscapes shaped by human movement and perspective. [However] in space, things move beyond human scale – you get rockets the size of 10-storey buildings, and they move into places where the human body can’t go. To discover how things come about you have to find new methods. There are huge amounts of documentary records, but they don’t even begin to describe what happened. It’s when you talk to people who were there, you get all kinds of stories that were never written down.

What do you find exciting about space technology?

The space age is often presented as the latest point in our evolutionary trajectory, with technology that is better and more perfect than what’s gone before, but that’s not always the case. Space tech is just as random and quirky as anything else that humans do. Machines are proxies for human behaviours and ideologies and things get made, or don’t get made, for political reasons. There are so many beautiful objects up there that are technological dead-ends, things that could have been developed further and weren’t. I love looking at what drives those decisions.

What about the stars and planets, do you have a favourite?

Venus is my favourite planet. Apart from being named after Aphrodite, the goddess of love, there’s something very sensual about Venus as a planet. It’s very hot, it’s a very extreme environment. It’s one of the most visible planets; I remember as a little girl I used to go outside and look for it. It appeals to me because as intellectual women, we’re often expected to suppress our sensual sides, so for me Venus is quite symbolic. As a planet she’s in your face, she says, “This is who I am, get used to it”. I feel a strong affinity for her – and of course, she’s the only planet not named after a male.

When almost all the planets are male, it suggests there is no place for women in space.

Space is absolutely gendered. You can see it in children’s clothes, children’s toys, children’s bedroom decoration. Space, like dinosaurs, is for boys. Around the age of six or seven girls start to feel the effects of this – they start to realise they’re not supposed to be smart, to be techy, to be scientific. It’s one of those watershed moments – like at puberty, when girls realise that their entire social world will be structured around how boys react to them.

Interview with Alice Gorman by Ute Junker

Photos_ Supplied