The Women-Only Hotel That Changed The World

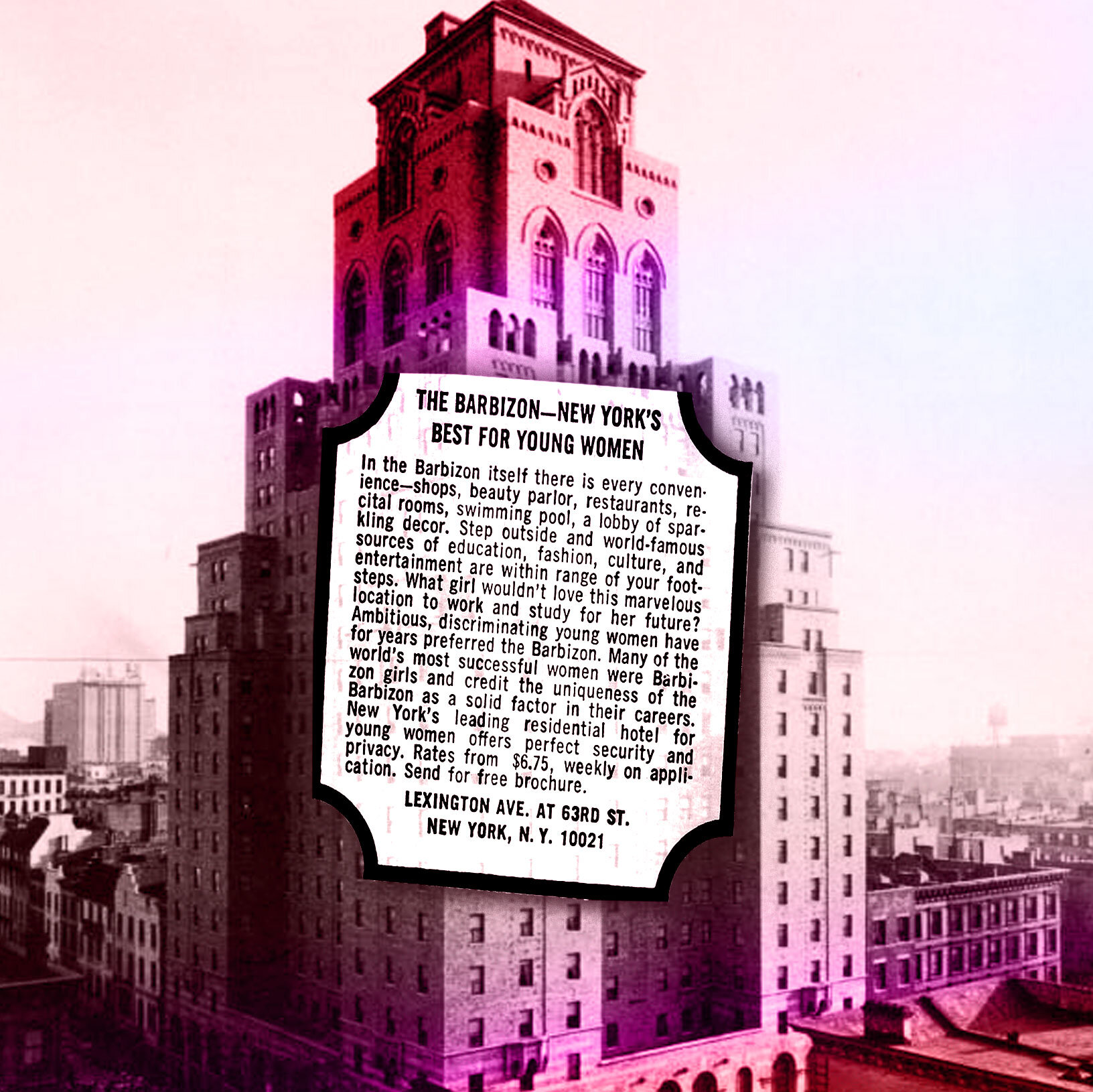

In post-war New York there was only one place to stay if you were a young woman hoping to make your mark in the city. The Barbizon hotel was home, temporarily, to some of the 20th century’s biggest names from Grace Kelly to Joan Didion and Sylvia Plath. In this extract from The Barbizon: The New York Hotel That Set Women Free by Paulina Bren, we meet some of the characters who made the Upper East Side establishment their launch pad.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, requests for rooms at the Barbizon grew exponentially, the hotel manager Hugh J. Connor, with the help of assistant manager and the front desk’s eagle eyes, Mrs Mae Sibley, were now finding it a challenge to co-ordinate all the various reservations and check-in-check-out dates. Together they calculated that close to “100 famous fashion models, radio and television actresses” along with many more “stage and screen hopefuls, girls studying art, music, ballet and designing” were residing at the Barbizon at any given time.

Shirley Jones, later to star as David Cassidy’s on-screen mother in The Partridge Family (as well as his real-life stepmother), was dropped off at the Barbizon by her parents with $200 in her pocket. She had spent a year as “Miss Pittsburgh,” followed by a year acting at the Pittsburgh Playhouse. The next step was of course New York and the Barbizon. Sure enough, she walked into the weekly open auditions for all the Rodgers and Hammerstein Broadway shows, and the casting director, upon hearing her sing, sent everyone else home. Judy Garland insisted her daughter, Liza Minnelli, stay at the Barbizon and drove the staff crazy by calling every three hours to check up on her Liza, and if she wasn’t in her room, they were ordered to go find her.

The post-war Barbizon now staked its claim as New York’s “dollhouse,” as the place to spy shapely young females, made all the more alluring by being tantalisingly out-of-reach in their sequestered, women-only lodgings. The dollhouse was a place many men dreamed of. Even J. D. Salinger, the elusive author of the 1951 novel Catcher in the Rye, hung about the Barbizon coffee shop to pick up women.

Carolyn Schaffner, of Steubenville, Ohio, looked a lot like Audrey Hepburn. Pale skin and black hair that shone as if it had been brilliantined. She wanted one thing: to get out of smog-covered Steubenville, to say goodbye to her stepfather, who considered her an unpaid caretaker to his children with Carolyn’s mother.

Carolyn understood that dreams needed to be worked at. She studied fashion magazines, models’ expressions, hand gestures, and when it was time for the town to choose its Queen of Steubenville in celebration of its 150-year founding, Carolyn canvassed. As the winning queen, riding in the parade, hoisted high, waving to the people of Steubenville, she was offered the choice of a trip to Hollywood for a screen test or five hundred dollars. Carolyn wanted escape, not stardom, and chose the cash. It took Carolyn Schaffner one full day to travel by train from Ohio to Penn Station in New York. She did not know much about New York, but enough to flag down a yellow cab and ask for the Barbizon Hotel for Women. It’s what all the fashion magazines she studied so earnestly told her: the Barbizon was the only place to stay for a young girl new to the city.

Young women of varying backgrounds and means slept within the walls of the Barbizon. There were the Carolyns, the girls from nowhere, both literally and figuratively, but there were also the debutantes.

In the infamous documentary film Grey Gardens, as Little Edie Beale and her mother Big Edie Bouvier, cousin of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, battle it out in their derelict Hamptons home among many cats, Little Edie longingly reminisces of her time at the Barbizon. She lived there from 1947 – when Carolyn also arrived – to 1952, dabbling in modelling, waiting for the chance to make it in show business.

But it was the Carolyns, not the debutantes, who truly understood that their time at the Barbizon offered a finite window of opportunity – while they were still young, pretty, desirable, driven. Those assets could lead to secretarial positions, to modelling gigs, to acting jobs. Yet all the women at the Barbizon shared the ultimate goal: marriage.

“The post-war Barbizon now staked its claim as New York’s ‘dollhouse,’ as the place to spy shapely young females, made all the more alluring by being tantalisingly out-of-reach in their sequestered, women-only lodgings.”

There was one young woman Carolyn had seen leaving the Barbizon: a round-faced teenager with light brown wavy hair, in a black coat and matching hat with blue flowers attached. She saw her again as she was unlocking her room on the ninth floor. In fact, the young woman was in the room right next to Carolyn’s: they were neighbours. Carolyn reached out her hand. “I’m Carolyn from Ohio, Steubenville,” she introduced herself.

“I’m Grace, Grace Kelly, from Philadelphia,” said the other girl.

She said she was studying acting at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. Grace and Carolyn became fast friends.

Carolyn's first serious job was a two-page spread in Junior Bazaar, where she was surrounded by the accoutrements deemed necessary for a young wife – dirty laundry, laundry basket, iron, ironing board. This first big modelling job quickly led to more bookings, until she was working steadily. Carolyn was soon on the cover of McCall’s, photographed by a still relatively unknown photographer by the name of Richard Avedon.

It seemed Carolyn had made it; she had accomplished what she had set out to do when she boarded that train from Ohio to New York. She then made the kind of gesture that marks the triumph of a small-town escapee: she sent her mother the latest refrigerator model to replace the ice block in the larder. It was also a four-letter gesture to her stepfather, of course. She was saying it loud and clear: she, the newly renamed Carolyn Scott, barely 20, could provide what he would never be able to, or be willing to.

Grace Kelly had watched with some envy as Carolyn became financially independent, certainly not rich but with enough to pay her weekly hotel bill, as well as lunches and dinners out or at the coffee shop, and all the various things that models needed to stay looking good. Although she had nothing to worry about because her room at the Barbizon was paid for by her parents — always in full, always on time — Grace wanted to know she too could support herself. And it wasn’t just Carolyn; there were lots of other young women at the Barbizon who were benefiting from Madison Avenue’s demand for a pretty face and a slender figure. Advertising was one of the fastest growing industries.

In 1956, Grace Kelly had married the prince of Monaco in a wedding that dominated world news. In a few short years, she had gone from acting student staying at the Barbizon Hotel for Women to famous actress and Academy Award winner to love interest of Prince Rainier III of Monaco. In marrying him, she officially retired from acting at the age of 26. Thinking back on the 1950s, one of her bridesmaids would say: “Did I think at all about the future? Not at all. Not a bit about ours nor even Grace’s … it was the ’50s. From where we stood, we were pretty sure that as long as we looked the right way, married the right man and did and said the right things life would unfold before us as easily and enjoyably as it always had.” Marriage was still the goal, and the Barbizon, the dollhouse, was its most coveted antechamber

The 1950s is a decade sometimes remembered with rose-coloured glasses, a time, some say, when America prospered as it had never before nor has since. Yet the 1950s were bursting with contradictions, with the unspoken, with pretence, some of which would lead to tragedy. Grace Kelly, actress and princess, would famously die as her car pitched over the side of the mountainous, winding road in Monaco. Carolyn Scott, the model, would succumb to mental illness and live out the rest of her years in a homeless shelter in Manhattan. Janet Wagner, Mademoiselle guest editor and model, would marry a man who caught a flight to a business meeting one day and never came back: he would be accused of exploding the commercial plane he was on in a desperate act of suicide, taking everyone with him.

The prevailing wisdom for women of the 1950s, the notion that marriage meant success or at least security, often proved false. For many 1950s residents of the Barbizon, their small rooms, hard beds, frantic dress-ups before a date, late-night conversations with friends, even chidings by Mrs Sibley, would become touchstones of nostalgia. They had understood their time at the Barbizon as a short window of opportunity that would usher them toward the ultimate goal of marriage, but in fact, looking back, that window — and the female camaraderie and independence that defined it — turned out to be a highpoint.

An edited extract from The Barbizon: The New York Hotel That Set Women Free by Paulina Bren

Want more Tonic delivered free to your inbox? Subscribe here